| Lisa Tellez | Spring 2003 |

| History 1302 | Hines |

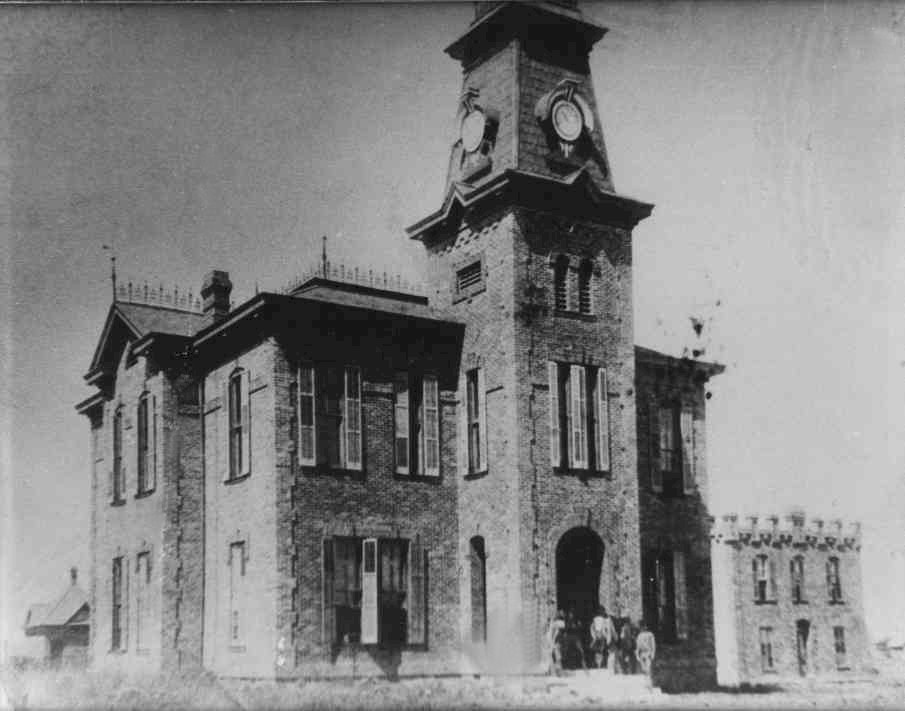

Cotulla

is located 27 miles north of Encinal on U.S.

Interstate Highway 35 in the northwestern part of

La Salle County

. In 1871, Joseph Cotulla, a Polish immigrant

turned developer, staked out large tracts of land on the Nueces River

in La Salle County. In 1870, Cotulla brought his family to live

on the land in a new stone home. Cotulla then gave some of the

land to the International Great Northern Railroad in order to induce

the railroad to stop on his land. In the beginning, the town consisted

of a handful of one and two-room lean-tos with absolutely no conveniences

for residents to enjoy. In 1882, the depot was built and Cotulla

began selling lots in the new town that, according to John Leffler of the

Texas State Historical Association, Cotulla "modestly named after himself."

By the end of the year, the town of Cotulla had acquired a post

office, a jail, a general store, and a hotel. In 1883, the town

of Cotulla became the county seat. Building intensified, and the population

began to grow. By 1890, Cotulla consisted of 1,000 residents, two

churches, a cotton gin, a corn mill, a bank, a saloon, two newspapers,

and three general stores. In 1885, a school was built for Cotulla’s 135

students. By 1892, Cotulla gained three more general stores, two more

saloons, a meat market, two grocery stores, and a daily stage service to

complement its railroad connection.

Establishing a civilized, comfortable environment in early

Cotulla was no easy task. Living conditions in the early days of

Cotulla were rough, not only because of the rugged, isolated terrain,

but also because of the lack of order. According to the Texas

Handbook Online, story has it that railroad conductors announced the

Cotulla stop by shouting “Cotulla! Everybody get your guns ready.”

At least 22 townspeople are said to have lost their lives in gunfights,

including three sheriffs. The terrain consisted of thick brush,

and cow trails barely wide enough for the passage of a wagon.

Despite the enormity of the task, though, by 1954 Cotulla would evolve into a thriving town that would grow to 4,425 residents and 92 businesses-perhaps so much larger at that time due to the flourishing economy that resulted from the discovery of oil. Before, in 1904, telephone service was installed, and in 1914 the franchise for Central Power and Light Company was granted. By then, 1,800 people resided in Cotulla, and the town boasted two restaurants, two banks, three hotels, a movie theater, and an ice plant. In 1915, the city water well was drilled and a deep, pure stratum of artesian water was found. According to the La Salle County Historical Commission, “Cotulla then became known as the ‘best watered’ small town in Texas.” In the mid-1920s, new elementary and high schools were erected, and by 1931 Cotulla had a population of about 3,175 residents, with 75 businesses. A public library was founded in 1937, and by 1941 Cotulla had 3,633 residents and 80 businesses. In 1947, 54 businesses were reported, and in 1949 the town built its first airport. By 1974, two thirds of the town’s population was Hispanic. In 1982, Cotulla had a population of 3,912 and 74 businesses. In the early 1980s, Ida and Ben Alexander donated the Alexander Memorial Library, and the La Salle County Historical Commission now sponsors the Brush Country Museum in the center of town. In 1990, the population of Cotulla was 3,694. Cotulla's estimated population in the year 2000 was 3,614.

The Untold Story:

Cotulla's economy has been largely based on sheep and cattle ranching, as well as farming. Unfortunately, while many of our Texas counties have been named after revered men who possessed large tracks of acreage for grazing and farming, few remember the poverty stricken Chicano men women and children who supplied the blood, sweat and tears necessary for the farm and ranch owners to profit. In most historical accounts of La Salle County, there is blatant disregard for Chicanos and the contributions that they have made to Cotulla, and to La Salle County. The Brush Country Museum, located in Cotulla, is very extensive, and quite impressive, yet Chicano names and faces are noticeably absent from the many rooms that are stuffed with old documents, newspaper clippings, antiques and photos. During my visit, I found only two photos of Chicanos out of the thousands of items that were there to see, despite the fact that Hispanics have made up the majority of La Salle County’s population since the late 19th century. There is no mention in the Brush Country Museum of Jesusita Torres Tellez (1876-1962), the town midwife and herbal healer who dedicated her entire life to helping those who could not pay for doctors, or the fascinating techniques that she practiced. Nor is there any mention of the hard work and resourcefulness of the Chicano families who made Cotulla what it is today. There is no mention of their labor, or their beautiful traditions, such as the weekly festivities held in the Plaza Florita, where for generations Chicanos have danced to the sounds of Mexican music, and sold food in order to supplement incomes. Hardworking and industrious, these people survived tremendous hardship with positive attitudes, a strong commitment to family and employers, and the determination to never give up hope.

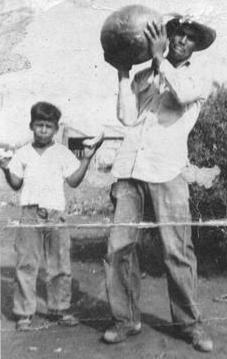

Nevertheless, there is no mention by the Brush Country Museum, or its founders, the La Salle County Historical Commission, of plight of the Chicanos who worked the farms and ranches. As in many other areas of south Texas, land owners became wealthy by taking advantage of the Chicanos that they oppressed with the dishonest methods of sharecropping. According to Elena and Chucului Santos, migrant work was often necessary due to a poor season on the farms, or in the frequent event that the sharecroppers were jilted by the land owners. It was not uncommon for an entire family to work all season and, to their despair, end up owning the landowner money rather than being paid. On such occasions, in order to survive, half of the family would remain in Cotulla to work the owner's farm, and the other half would travel to other areas of the state and country to labor as migrant workers. Sadly, families were often split for long periods of time. There was much hard work and despair for barely enough pay for food. The Santos family spoke of being paid only about $30 a week in the late fifties for the work of the entire family. The family basically worked to eat, and ate in order to work. My husband, Roland Tellez, sometimes traveled to Cotulla with his brothers as a child where he stayed with his grandfather Jose and helped the families with the watermelon harvest. The children would form long assembly lines and pass the watermelons to the trucks as they slowly rolled through the patch. Roland hated ending up in the front of the line because he had to toss the heavy watermelons up to the man who stood in the truck stacking them. His neck, back and arms would ache for days. One day Roland's mother, Dora Rodriguez Tellez, returned to Cotulla to retrieve Roland and his brothers. She became angry when she set eyes on them. She said "You look so black!" Dora swore to never again allow her children to work in the fields. She vowed that no child of hers would ever again suffer the way that she had when she was a child. Dora kept her word.

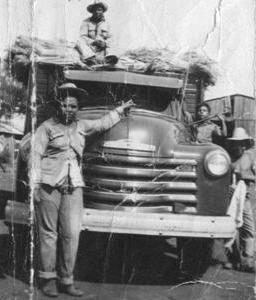

Cheme and Ernesto Tellez at the watermelon patch

Leaving in search of a better life was impossible, because the money necessary

for making a new start could rarely be saved. Throughout the history

of Cotulla, most farm and ranch workers lived on the land they worked.

If workers lost their jobs, they were rendered homeless. Few

ever knew the security of owning a home of their own. And the

cycle of poverty and oppression was never ending because Hispanic children

were unable to acquire an adequate education. Few Latino children

were able to move beyond the fifth grade in school, and most were not

even able to attend regularly, if at all, as they were needed to help

work the farms and ranches. An entire family of workers was required

to complete the overwhelming workload necessary in order to be paid.

The "great pioneers" of La Salle county, the so-called "trailblazers",

became rich and powerful because of the sharecropping system, which

was a legal form of slave labor. Such oppression was accepted as

normal and decent by the Anglo population because of the the racist views

in Cotulla and surrounding areas. Hispanics were seen by much of

the Anglo population as lesser human beings who lacked the intelligence

to live as anything more than mere mules for Anglos.

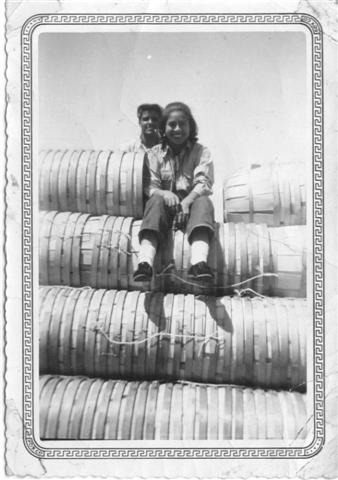

A Workday In The Fields

From left to right: None Tellez, Elia Patterson, Norma Patterson, Tony Patterson III, Chayo Tellez, Samuel (Cheme) Tellez, and Daniel Tellez

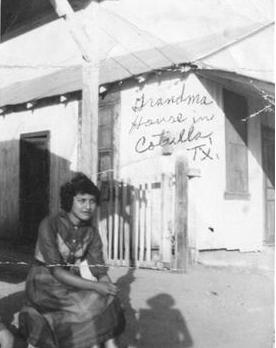

Segregation was a natural part of such discrimination. Cotulla did a good job of imitating Thomas Jefferson's habit of keeping his slaves and their living quarters out of sight in order to keep their plight out of mind. Throughout much of the twentieth century, those Latinos who lived in town resided in the “Mexican side” of Cotulla, which was literally separated from the Anglo population by the railroad tracks that cut through town. On the “white side” of the tracks, beautiful homes were perched on carefully kept lawns. Traveling to this side of town was like stepping into an episode of Andy Griffith. The streets were paved and lit, time passed slowly, and contentment filled the air. But on the other side of the tracks, the “Mexican side” was a far cry from the comfortable, middle-class setting enjoyed by the Anglo population. While Central Power and Light Company did provide electricity to residents of Cotulla, most Latino families were not able to pay for electricity, and many did not even have access to it. Though the power company began business in Cotulla in 1914, Hispanic women were forced to heat the “sad irons” on wood burning stoves, even as late as the forties and fifties, according to those I have interviewed. A luxury for these women was having more than one iron so that the second could be heated while using the first. Progress was so slow for Hispanics that Children were forced to do the laundry-building fires, hauling water, boiling clothing, scrubbing, wringing, hauling more water for rinsing, then hanging-because their mothers could not keep up with the overwhelming workload which resembled that of 19th century pioneers. The “Mexican side of town” sported narrow, one-lane dirt roads, and Hispanic families were forced to live in the small shacks that were crammed into tiny lots. Cars were barely able to pass between the front fences of some. I recently traveled one of these streets and thought I had mistakenly turned down an alley, until I saw the front doors of the tiny, dilapidated homes. Some seem to have been pieced together with whatever building materials owners could manage to scrape up.

Above right is the house that midwife Jesusita Tellez lived in.

Jesusita lived better than most Hispanics in Cotulla.

The unknown woman is sitting on the porch of the home next door.

There was an unwritten law in Cotulla that Hispanics were not to cross the tracks for any reason but work. When my husband Roland visited Cotulla as a child, he longed to take the money he had saved and see a movie. He "didn't want to go to the theater Mexicano (Mexican theater)," but instead "longed to visit the beautiful theater on the white side of town where the good movies were showing." He was forbidden by his grandparents to attend the theater on the "white side of town" because, as his grandfather put it, he "would surely be beaten by the white people for daring to do so."

Elena Tellez Santos at the "Mexican theater"

Schools were segregated as well. Records indicate that

in 1896 and 1906, a separate school was used for just 15 black

children. By the mid-twentieth century, things had not changed

much. Welhausen, the old, inferior school designated for

“Mexicans,” was blatantly unequal to the newer and better equipped school

that was provided for Anglo students who made up a much smaller portion

of the population. In Cotulla, education was seen as something for Anglo

children who “could do well in life.” Diane Lopez translates for

her mother, Teresa Tellez Patterson:

Okay. Back then, the white people had to go to school. That was like something that they had to. But since these people were permitted, the Mexican Americans were permitted to go to school, but it wasn’t something they had to. It was by choice. If they went, fine. If they didn’t, fine. There was no obligation, and they did not have to attend school at all.

I asked:

So, I’m assuming then, that the, kind of the, the opinion was that, um, uh, Hispanics weren’t really going to…

Diane interrupted:

to prosper.

In Cotulla there existed an assumption that Chicano children

could only continue working the farms and ranches of Anglos once grown,

and that Chicana women would simply get married, keep a home, and raise more

children to work the farms and ranches. The opinion shared was that

Chicano children did not need an education.

Diane again translated for her mother, Teresa:

She said that she went all the way until she was in the fourth grade, but if she went one month a year, that was a lot for her to attend school. She said instead they would have her work. And if her mother was scheduled to have a child that year, then she would definitely have to go home and stay with the grandma at the ranch because she had to take over the obligations, like the cooking and the cleaning, and the ironing, and stuff.Teresa is here referring to her grandmother, Jesusita Tellez, the town midwife. If Teresa's mother, Guadalupe Tellez, was expecting a child, Teresa would move to Jesusita's home and take on many of Jesusita's chores so that Jesusita could frequently walk the many miles to Guadalupe's home to provide prenatal care.

It is no surprise that there was little concern regarding the lack of adequate living conditions and appropriate education resources for Hispanics in Cotulla. The sisters discussed their memories of the racism that occurred in Cotulla, which they describe as “a prejudiced little town.” The ladies told of how the “Mexicans” were treated poorly by “the white people” of Cotulla, and how they were accustomed to believing that they were not meant for anything more than working the farms owned by Anglos. Hispanics were conditioned to know their place. Len recounted how the Chicanos were treated by law enforcement officials in Cotulla.

Oh, yeah. And what the, what the, the, the law over there, like the Sheriff, and like the, the… What was the brand new one? He was the Mayor, or what was he?

It was the Sheriff and the Judge.Len continues:

I don’t know what the… He use to go and pick up, he went to use to go and whoever did wrong, uh, they did something wrong out there—if they were Mexican boys, they took em to jail, and they peeled their heads real ugly. They cut their hair real ugly. They did, they did, they didn’t cut it like they’re using right now. You know there are a lot of bald headed boys that have good, nice haircuts? No. They give traskiladas (chops] here and there. Ugly. Yeah, to humiliate them—ugly. That’s why my brother, that lived over there, Samuel, he had, he use to hate them, cause they did it to him. Just for a little thing he did. But if the, if white people do it, they didn’t do it to them.Diane:

They didn’t touch em. They just waited for them to be released.Len:

They just put em to jail, but they didn’t get bald headed or nothing like that—cause they were white people.I asked the ladies if the police were ever violent, and Len responded:

Yeah! If they get, sometimes they get, you know, if they say something to them back or something. Yeah, they all did that. They use to hit em, the people. Yeah, cause, for talking back to them, something, but I, I didn’t heard about doing that to the white people, but to the Mexicans, they surely did. Uh huh, they just stood there and sometimes they told them “and you better say it was your fault” even if it wasn’t their fault, cause if you don’t, you’re gonna get more in trouble. That’s why my brother, that went to the prison, he said “well I had to tell them, cause if I didn’t do it they were going to give me more years over there.” So, so that, that’s the only brother that my dad had uh, you know, problems with him. And he said “what did you say?? You weren’t the one that were!” “Well, they told me to say that.”I asked:

So, he was innocent, but they told him to say that he did it?Len responded:

He didn’t have a choice. But, you know why? And that’s why. Because they knew that the other people from the other boy that had the, that had the vehicle and everything, they had money. And I think they took money out of them, and my dad wasn’t that wealthy so, so he couldn’t pay that much so, so they had to take that other one, the one that didn’t have no money. That’s the way it was. Now, in these days, Mexican people, over there, they’re speaking out and they’re something better, and now Cotulla’s getting better.Len also discussed segregation at football games:

I, I , I don’t know, but uh, uh, uh, when I use to go to the football games and everything, they still, they still have their section. They, they, they didn’t, like, they didn’t sit a white one with a Mexican. Like they use to... Everybody had a little section over there.Diane added:

I don’t think the white, older people, the parents would allow them—to hang around with Mexican children.I asked the ladies how this made them feel, and Len responded:

Down. I feel down! You know, I feel down, cause I said, “Why? We’re people like them, and, and we do lot of work for them and everything. Why do they treat us like that?

Even today, the inequity continues. U.S. Census records

indicate that in the year 2000, Chicanos made up nearly 80 percent

of La Salle County's population, yet the records also indicate that

somewhere between 0 and 19 percent of farm and ranch land was owned by

Chicanos. The specific number was too low to record. This is a significant

point, because the basis of La Salle County's economy is farming and ranching.

The efforts of Chicanos to progress would never have worked in earlier years. Chicanos could rarely gain the capital needed to start a business, and public office was continuously dominated by Anglos as well, even though Chicanos made up the overwhelming majority of the population. The first Chicano judge listed by the La Salle County Historical Commission, Leodoro Martinez, Jr., took office in 1983. The Commission's records also show that no Chicano has ever served as clerk, and that the first Chicano sheriff, Jose T. Garcia, held the position from 1983 to 1984. Clearly, Chicanos had no voice. Chicanos were kept out of office in many ways. For one thing, Chicanos could not compete with wealthy Anglos in expensive campaigns. Additionally, since La Salle County farms capitalized most heavily on winter crops, many Chicanos migrated north during the summer in order to maintain income. This happened to be the time of year that elections were held in the county, which left most Hispanics out of the voting process. In a 1970 speech delivered in San Antonio, Jose Angel Gutierrez, leader of the Raza Unida Party, touched on the issue:

We were Chicanos who were starved for any kind of meaningful participation in decision making, policy making and leadership positions. For a long time we have not been satisfied with the type of leadership that has been picked for us. And this is what a political party does, particularly the ones we have here. I shouldn't use the plural because we only have one, and that's the gringo party. It doesn't matter what name it goes by. It can be Kelloggs, All-Bran or Shredded Wheat, but it's still the same crap.

These parties, or party, have traditionally picked our leadership. They have transformed this leadership into a kind of broker, a real estate guy who deals in the number of votes or precincts he can deliver or the geographical areas he can control. And he is a tape recorder-he puts out what the party says.

A beautiful example of this is Ralph Yarborough (Democratic senator from Texas). The only thing he does for Chicanos is hire one every six years. He's perfectly content with the bigoted sheriff and Captain Allee (Texas Rangers) and the guys that break the strikes in El Rio Grande City and with (Wayne) Connally (brother of former Texas governor John Connally) and all these other people. Well, he gets beaten, and he knows why. The Republicans, the Birchers, the Wallace-ites and all these people went over to support Bentsen in the primaries. Yet I just read in the paper this afternoon that he said, "As always, I will vote a straight Democratic ticket in November."

There is only one other kind of individual who does that kind of work and that's a prostitute. . . .

Four years ago, when the guy who is now running for commissioner in La Salle County in La Raza Unida Party ran in the Democratic primaries, it cost him one-third of his annual income! That's how much it costs a Chicano with a median income of $1,574 per family per year. With the third party it didn't cost him a cent.

On top of the excessive filing fees, they have set fixed dates for political activity, knowing that we have to migrate to make a living. We are simply not here for the May primaries. Did you know that in Cotulla, Erasmo Andrade (running in the Democratic primary for state senator in opposition to Wayne Connally) lost by over 300 votes because the migrants weren't there? In the Democratic primaries you're not going to cut it. In May there are only 16 more Chicano votes than gringo votes in La Salle County. But in November the margin is two and one-half to one in favor of Chicanos.

Later in the speech, Gutierrez added:

Did you know that not one of our candidates in La Salle County had a job the whole time they were running, and that they still can't get jobs? The same thing happened in Dimmit County. In Uvalde this is one of the reasons there's a walkout. They refused to renew the teaching contract of Josue Garcia, who ran for county judge. That's a hell of a price to pay. But that's the kind of treatment that you've gotten.

You've got a median educational level among Mexicanos in Zavala County of 2.3 grades. In La Salle it's just a little worse-about 1.5 grades.

The median family income in La Salle is $1,574 a year. In Zavala it's about $1,754. The ratio of doctors, the number of newspapers, the health, housing, hunger, malnutrition, illiteracy, poverty, lack of political representation - all these things put together spell one word: colonialism. You've got a handful of gringos controlling the lives of muchos Mexicanos. And it's been that way for a long time.

Even a rare Anglo politician who

cared about the plight of Chicanos could not help. One Anglo

person who grew up in Cotulla and wishes to remain anonymous because

“there are still very sensitive opinions about the earlier era,”

gave an account of an occurrence that smacked of

gerrymandering

, an illegal process that robs the oppressed

of a voice:

I graduated in 1964. It was the first graduating class where social activities were beginning to integrate. The LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) organization invited the Anglos to their graduation party. A small group of my friends and I went for a while. Kinda strange, because the cultural division still existed. In the next years to follow, the dividing line became more invisible. In my graduating class, many of the Hispanics went on to college and successful careers.

I wish Virgil Smith were still alive. He was the county commissioner of precinct one for over 20 years. The precinct covered the east side of the railroad tracks where most of the ‘Mexicans’ lived (that is what we called the population group, reflecting their cultural roots). Virgil was easily re-elected each election year. He fought for programs to help the Mexican families during the drought of the 1950s, which made him unpopular with some of the Anglos. He battled in Commissioner’s court to implement a good program. I can remember helping him hand out basic food items and seeing fellow students and their families in line. It made a huge impact on me for my entire life. It really put a face on the need.

Virgil was a stubborn man when it came to what he believed in. The Anglos could never vote him out of office, but in the early 60s, they had the precinct lines redrawn and he lost east Cotulla. Thus, he was voted out of office. Strangely, he lost to the same man that he beat out to come into office years before.

Virgil majored in Spanish in college and could speak it with ease. He worked (in construction) a lot of "wet backs" from Mexico out in the countryside. He became real good at different dialects in Mexico. He would have been able to give an Anglo view of the cultural differences during the 40s, 50s and 60s.

Because most of the Chicanos worked on farms and ranches in the fifties,

and were already very poor, they were devastated by the drought.

Unlike the owners that they worked for, the Chicanos had nothing to sell

when there were no crops to farm, nor did they have a savings to fall

back on. It is tragic that most of those who profited from the

cheap labor of the Chicanos could not see fit to help them out of

the desperate situation that they themselves put them in. Even

loans and credit were not an option. According to the Tellez

sisters, all but a handful of the town's businesses were owned by Anglos

who would not extend credit to Chicano families because “they never knew

if you were going to earn enough to pay them, ” says Diane Lopez.

Chicana women of Cotulla have had a particularly difficult struggle with discrimination, as they were forced to endure not only racism, but sexism as well. While Chicano men could at least enjoy dignity among their Chicano peers, Chicanas were forced to endure degradation in both the Anglo and Chicano portions of society. In 1886, Cotulla had a debating society which on one one occasion discussed the topic “Should the education of a woman be co-equal of that of a man?” Fortunately, in the twentieth century the inferiority stigma attached to women-whitewomen, at least-began to wear away. However, Chicanas did not enjoy the same progress. Young Chicanas were forced to work not only the farms and ranches, but also to share the household chores, which were grueling due to the lack of modern conveniences. Many took on a third responsibility as well, cleaning spinach for a local supplier.

Elena Santos told me of

the raw skin, lacerations and blisters that covered her burning, throbbing

hands the majority of time throughout her childhood from picking cotton and

shredding broomcorn. It is no wonder that most girls were not able

to attend school regularly. Few gave much thought to this, though.

Girls were expected to prepare merely for the care of a husband and

children, and nothing more. Elena Santos had this to say:

Yeah, and my grandma use to tell us “as long as you learn how to write your name, that’s enough. What you have to do is learn how to cook, how to sew, and what to, how to do your chores in your house, and that’s it. That’s your responsibility as a lady.”

Len, as a teenager, stands in front of the work truck catching her breath after a hard day of bundling and stacking itchy broomcorn in the heat. Younger brothers, Cheme (center) and Daniel (far right), labored with Len and their father, Jose Tellez, who is seen resting on top of the bundles before the trip to the buyer.

Social rules were also much different for Chicana women.

Most Chicanas were considered the “property” of their husbands and

“had no say” in their marriages, nor were most Chicana wives allowed

to take a job, though men expressed that the husband had all of the authority

in the family because “he made all of the money.” The money

that wives made making cheese, sewing, etc., was generally not credited

to them as worthy of note. Some wives were forbidden by their husbands

to earn money in such ways. But some, like Teresa Patterson, did

so secretly in order to provide small luxuries for their children, such

as an occasional popsicle. Additionally, Chicanas tended to be

labeled as loose women if they were seen in public without either their

husbands, or some other escort deemed appropriate by the husband.

Anglo women, on the other hand, could do as they pleased and still be seen

as respectable by the townspeople. Elena commented:

Well, in those times, the way we were treated, I wish I was a white lady. They were treat right. Cause, since my husband start working in the ranches, there was this couple that they were white people. And the man took up all right in the morning, this man that we live over there in the ranch—his name was Donald Jordan—and he has offices over there in Cotulla. He traveled from Millet to Cotulla every morning. And he can go to his office, and come in the night to his house. His wife can go anywhere she wanna go. Sometimes she come to San Antonio cause she has her mom over here in San Antonio. And she went and telled me, eh, “Tomorrow I ain't gonna be here. Go and feed my dog and do this and do that.” And she can come and stay over here with her mom two or three days, and she didn’t get a label.

Diane added:

And we think back, and we, I’m sure we’ve all seen the movie Roots, you saw then. Remember, the one lady went into town, got her groceries and stuff, and she was allowed to go on her own. And, of course, if you had seen the black woman go into town on her own, then she could be for sale.

Diane speaks of her mother, Teresa:

She wasn’t allowed to go to the grocery store. What she did is she had to order it by phone. By then they already had a phone. The groceries was brought to their home and, and she would, she wasn’t allowed to pay for it either. Once my dad came off the truck, cause he was a truck driver, then he would come and go sign wherever, and he would pay.

The tendency of many Anglos to look down on Chicanos had

a tremendous impact on the way that Chicanas in Cotulla were treated

by their husbands, and society as a whole. It is conceivable

that Chicanos were driven to fiercely protect every ounce of dignity

that they could cling to, under the circumstances. It is also

understandable, though not acceptable, that the reputation of Chicana

wives would be so closely guarded by their husbands against any possibility

of slander, which would in turn lead to further indignation. On the

other hand, one wonders whether or not-like so many other stereotypes of

Chicanos-there also existed some false notion that Chicana women were

somehow prone to inappropriate behavior, just as some whites incorrectly

believed that Chicano men were prone to certain character flaws, simply

because of their Latino heritage. Such haughty ignorance resembles

that which gave birth to former laws prohibiting black men from looking

at white women, and black barbers from cutting a white woman's hair-the erroneous,

arrogant assumption that black men were "prone to a lack of self-control

regarding sexual desire." The ramifications of such ignorance

are still being seen, however things are changing. Even older

Chicanas are beginning to rise up against the gender discrimination suffered

by the Chicanas of Cotulla. Elena Santos, having grown tired of

the sexism, speaks of her stand against not being able to shop and run

errands without her husband:

I use to do like that, and, and, and then I said, “Why am I in the prison? Why, if I don’t do nothing wrong when I go do my things, why do I suppose to be just inside over here—doing what I don’t suppose to be doing—when, when I need something to do, waiting for somebody to do it for me?” I said, “No, no, this is going to stop. I’m gonna go do whatever I wanna do. Uh, huh! And I gonna be at my house when I suppose to be in my house, but I gonna do whatever I wanna do! Cause I know I doing what I need to do. I’m not doing nothing wrong. Cause I don’t have to be afraid of nobody!"

Things were very difficult for Chicana women, but even terrifying for a young, unwed mother. According to Len Tellez, on one occasion, Jesusita was caring for a young, unwed, expectant mother who was so destitute that she could not care for a child. The girl was terrified of the shame of being an unwed mother, and especially dreaded the thought of giving birth to a girl who would be able to do little to help support herself in later years. As she endured the pains of labor, the desperate young girl asked Jesusita to throw the baby down the hole in the outhouse if it was a girl. Upon delivery, Jesusita discovered that the baby was indeed a girl. Overwhelmed with compassion, Jesusita asked the young mother to give her the baby. The girl agreed and Jesusita gave the baby to relatives, Mr. and Mrs. Panchito Tellez, who could not conceive a child of their own. The happy couple named the baby Siria Tellez.

There has been no closure for Chicanos in Cotulla-no reconciliation for those who have been disregarded and devalued. The plight of Chicanos in La Salle County has been so excluded from historical accounts that it is difficult for younger generations to learn the dark history of how La Salle County became the thriving farming and ranching community that has. The work of the Chicano people of the past 150 years ensured the wealth and success of the renowned Anglos who are so highly esteemed, yet Chicano names, faces and traditions have been overlooked, lost in the shadows of their wealthy oppressors. This is among the greatest of tragedies, for the history and culture of Chicanos in Cotulla and surrounding areas are rich and beautiful testimonies of the warmth, honor and integrity of the hardworking Chicanos who made La Salle County what it is today. Their sacrifices and resourcefulness are most worthy of praise. Somehow, much of society has adopted the idea that power and wealth are the measure of a man. In reality, though, the character displayed by the hardworking Chicano families of nineteenth and twentieth century La Salle is the epitome of what every human should aspire to be. How sad that so many historians have missed such a profound truth.

"It's ironic that those who till the soil, cultivate and harvest the fruits, vegetables, and other foods that fill your tables with abundance have nothing left for themselves."

"Our very lives are dependent, for sustenance, on the sweat and sacrifice of the campesinos. Children of farm workers should be as proud of their parents' professions as other children are of theirs."

--Cesar Chavez

To read

more of the interview with Tere, Nena, Len and Diane,

click here

.

If you have any historical information, documentation or photos that you would like to share concerning La Salle County Chicanos, please contact Lisa Tellez .

WEBSITES:

Excerpts From a May 4, 1970 speech in San Antonio by Jose Angel Gutierrez,

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

John Leffler. La Salle County . Handbook of Texas Online at http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/index.html. This is an excellent account of La Salle County's history, and of the contributions of Hispanic laborers to the growth of the economy. Best of all, Lefler speaks openly about the oppression and racism endured by Chicanos in La Salle County and Cotulla, and accurately shows the zealous pursuit of wealth and power that was displayed by some of the early prominent figures of the area who have been immortalized as heroes. Leffler includes economic, agricultural and even political history, while avoiding a sugarcoated, upper-class bias.

The La Salle County Historical Commission. History of Cotulla . Historic District at http://historicdistrict.com/. A brief summary including names of prominent founders, dates, and significant places in Cotulla's history. The page includes a photo of the first map of Cotulla, and a circa 1886 photo of Front Street, block 4. The writer gives a description of the town's beginnings, and notes prominent business owners and investors of the time. However, the writer falls grossly short of balance by the complete omission of the Chicanos who contributed to the founding and growth of Cotulla. The reader who does not know better is left to believe that there were and are no Chicanos in the area. Furthermore, the writer disregards the plight of the poor, failing to mention the work of the men and women who were the lifeblood of the area-the Chicano laborers who made it possible for the community to thrive.

The La Salle County Historical Commission. History of La Salle and Mc Mullen Counties . Historic District at http://historicdistrict.com/Genealogy/LaSalle/history.htm. A historical account of the La Salle County area, from 1716 to current. Also includes an account of the history of farming and ranching in La Salle county, including the names of past prominent farm and ranch owners and their descendants. But, again, the writer omits any mention of Chicanos.

The La Salle County Historical Commission. La Salle County Records . Historic District at http://historicdistrict.com/Genealogy/LaSalle/history.htm. The La Salle County Historical Commission actually does a very good job on this one. All sorts of records can be accessed here, including: 1870 La Salle Census, 1880 Census Index, 1880 La Salle Census, 1900 Census Index, 1900 La Salle County Census, Confederate Pensions, Texas Death Index, County Lookups, La Salle Marriage Index, Obituary Index, Obituaries, Probate Index, and WWI Discharges.