TRANSCRIPTION

What were you doing before America entered the war?

America entered

the war with Japanese intervention on December 7, 1941. And before that I was

going through elementary school, and I remembered in elementary school, I took

naps lying on the floor, this is in aside. I then went to elementary school at

the training school that was called for Arkansas A&M, which is now the

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. I spent one year at Merrill High School in

the year 1936-37. In 1937 we moved to Little Rock, and I went to Dunbar High

School, an all black high school and all black teachers, who were wonderful

people, wonderful motivators and I finished in '42. That's what I was doing…"

Before the war… "Um huh.".

Maybe you can tell me a little bit about your name Granville?

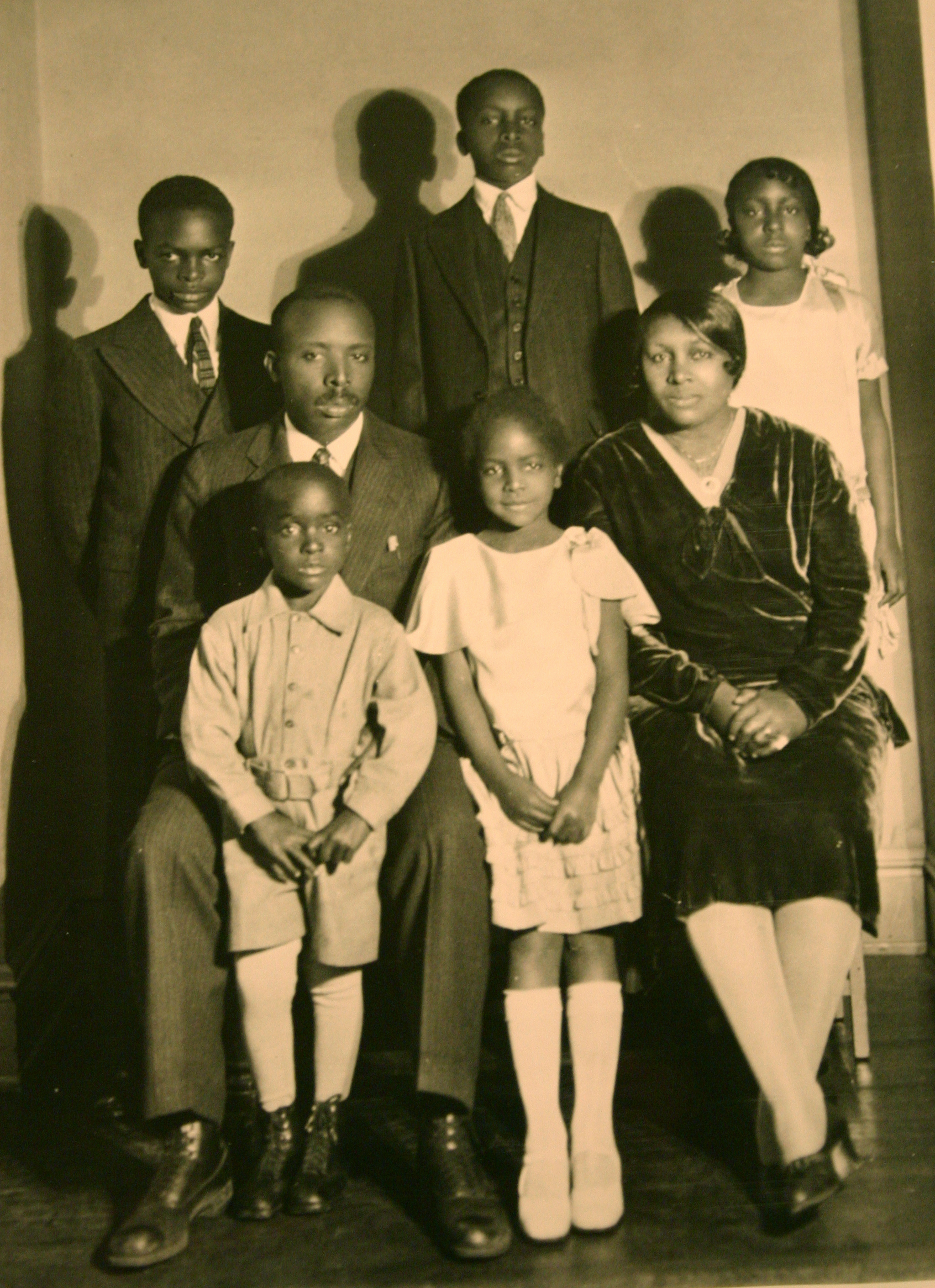

Oh yes, I like my name. And how it came about, my mother

was a unique person; I'm amazed at my mother. I'm the fifth child of her five

children, and she had hopes for her children's. And I'm her fifth child and she

wanted this child to be a musician. And so much so, if this child was a girl,

she was going to name it Marian Anderson Coggs, after the contralto Marian Anderson

who sings with Eleanor Roosevelt at the Lincoln Memorial. And from Samuel Coleridge

Taylor, who's a black musician, he actually was only half black, but the

black people claim him, that's what she wanted to name me. But I'll cut to the

chase, at a meeting, an evening meeting, where my father was the speaker and his

father was in the audience, he described his family and one in the oven as he

described me. And his father got up and called my father, and said, 'Doug, if

it's a boy name him after my father. His father was named Granville. And I don't

where Granville came from, but his father was a slave and so when I was born my

mother got half of her wish and instead of named Samuel Coleridge, I'm named

Granville, but um, my middle name, yea, she got part of the musician's name

Samuel Coleridge Taylor, my middle name Coleridge, after Samuel Coleridge

Taylor. And my mother got part of her wish, it's a part of reality, and hard for

me to realize, but tonight is March the 12th, 2006 and on March the 31st this

Granville Coleridge Coggs will be singing with the San Antonio Master Singers with the

San Antonio Symphony and the San Antonio's Children's Chorus in Carnea Burana,

so he's something of a musician.

Oh yes, I like my name. And how it came about, my mother

was a unique person; I'm amazed at my mother. I'm the fifth child of her five

children, and she had hopes for her children's. And I'm her fifth child and she

wanted this child to be a musician. And so much so, if this child was a girl,

she was going to name it Marian Anderson Coggs, after the contralto Marian Anderson

who sings with Eleanor Roosevelt at the Lincoln Memorial. And from Samuel Coleridge

Taylor, who's a black musician, he actually was only half black, but the

black people claim him, that's what she wanted to name me. But I'll cut to the

chase, at a meeting, an evening meeting, where my father was the speaker and his

father was in the audience, he described his family and one in the oven as he

described me. And his father got up and called my father, and said, 'Doug, if

it's a boy name him after my father. His father was named Granville. And I don't

where Granville came from, but his father was a slave and so when I was born my

mother got half of her wish and instead of named Samuel Coleridge, I'm named

Granville, but um, my middle name, yea, she got part of the musician's name

Samuel Coleridge Taylor, my middle name Coleridge, after Samuel Coleridge

Taylor. And my mother got part of her wish, it's a part of reality, and hard for

me to realize, but tonight is March the 12th, 2006 and on March the 31st this

Granville Coleridge Coggs will be singing with the San Antonio Master Singers with the

San Antonio Symphony and the San Antonio's Children's Chorus in Carnea Burana,

so he's something of a musician.

During the war, many things were rationed. Do you remember doing

without anything?

"This particular Granville Coleridge Coggs, is an

optimist, we were without things, but I don't remember doing without anything.

I don't remember being without anything… well, I know rubber was rationed,

gasoline was rationed, but it didn't

personally impact me and get into my world." So, it wasn't something that you

missed? "No, no, and somebody says, 'you can't really miss something that you

never had.' But apparently we had gas and rubber before. But, uh, my daily life

didn't change.

Before you joined the military, what were your thoughts on the

war?

Oh, this was a war for survival. This was a war for survival. And

we were happy that it didn't occur any closer to our shores than Pearl Harbor.

But it was no question the Japanese, the Germans and the Italians were out to

destroy us, and the whole country was mobilized to prevent our destruction. So

the war was in my mind and also because I was approaching draft age and people a

few years older than I were already over there fighting in the war, and I soon

would be scheduled to fight in the war. So it was a war for survival.

What made you enlist in the military?

Oh, the reason that I enlisted

was because I was shortly going to be drafted, and I took an option to volunteer

for the Black Army Air

Corps, which got underway the first class graduated in 1942. And in 1943 was

when I was about to be drafted. One of the first members of the first class,

Herbert Clark, was from Pine Bluff Arkansas. And Richard Caesar had finished and

was flying, so I knew that there was an opportunity, for shall we say blacks

with the talent or capability, to instead of being in the infantry and

non-commissioned and low paying person, to possibly be a flyer, as an officer,

and as a respected person.

Had you ever thought of being a pilot before?

RNot really, but you

couldn't escape it from '42 on. These were heroes, 60 years ago, and certainly

even now. They, in particularly, the Tuskegee Airmen

that fought overseas, prevented white men bombers from being shot down and

also shot down a few German fighters. This was, and the recruitment that went

on, that was radio recruitment that says, 'Men of 17, you too can fly' and so

when I was 17, yea, you didn't even have to be 18, you could be 17 and enlist

and go through the aptitude test and could join the Black Army Air Corps.

What did your family think of you becoming a pilot?

Oh, my mother

was a cool person. But basically the environment in our house was, if you can do

it, do it. And if you think you can do it, you can do it. (laughs) And 80 years

later, that still rings true; I'm encouraged to do things beyond what I feel I

can do. And, Maud, my wife, is on the same page, she the encouragement right

now. I ran a mile today in 11:22 but my goal is to run it in 11, and her

encouragement was, 'You Can Do It.' (laughs) So, I didn't do it, but my trainer

coach, who I reached by cell phone, he congratulated me on running 11:22. He

said, 'That's good.' But, that was the environment. One, if you think you can do

it, you can do it. I think that's so important, yeah, you know the environment

was… I understand, it's hard for me to imagine that in some cultures and some

home environments they say, 'Oh, you can't do that!' That was heresy in my

house. (laughs) Yes, siree.

What were your first impressions of military life like when you

joined?

Well I went in on December 18th, 1943 in Camp Robertson, Little

Rock, Arkansas. That's also my wife's birthday, December 18th. And I was a

private, I got the uniforms. They first sent me to training at Kessler Field,

Mississippi, Biloxi, Mississippi. And this was in South America, segregated

south America. I went on that base and I was there for six or nine weeks, I

forgot exactly how long, but I never left the base because the base was an

island amix segregated black Mississippi. So I didn't go off the post for what I

felt white Mississippian's might do. And the environment of Black Mississippians

who lived, well I stayed six weeks on the post and never left that post. And we

were trained. I've forgotten exactly what basic training was, right? But I was

with the rest of the people, and coming from a household where I came from, if

anybody else could do it, I could do it. (laughs) So, we did it. And after 6

weeks, they sent me to Tuskegee Institute for college training, because my

aptitude test had qualified me for training as a flying officer, bombardier,

navigator or pilot. And my qualifications were higher to be bombardier. And so,

they had accelerated everything, previously to be a, to qualify, for pilot

training you had to have a college degree in engineering. At Randolph AFB, here

is where cadets out of West Point and cadets graduated from Texas A&M with

degrees in engineering; that's who got a chance to go to pilot training, and

learned, which was reinforced more recently that the first place that military

flying took place was here at Ft. Sam Houston, and that was in March, 1910. In

1910 here at Ft. Sam Houston and Actually Randolph AFB was constructed in 1930

and I saw movies, in 1935 I saw the movie named, West Point of the Air, it was

filmed primarily at Randolph

AFB, and I saw it in a segregated, in the balcony, a black balcony in Singer

Theater in Pine Bluff, Arkansas in 1935. As a ten or eleven year old black

fellow student I could never imagine myself being a flying officer.

Could you maybe describe a little bit of what your training was like at

Tuskegee?

Well here is the training program, and I can tell you what my

training chronologically involved. They sent me first to several months of

college training at Tuskegee

Institute, so we lived on the campus, in what was called the Emory's. The

Emory's are still there. And I took mathematics and swimming, and a few other

things. But after a few months of college training they sent me from Tuskegee

Institute, Alabama to college to Tyndall

Field, Florida for Aerial Gunnery Training and I sent six to nine weeks

qualifying as a Aerial Gunner, 50 caliber machine guns,

because I was slated to become a bombardier, but before you could go into

bombardier training you had to qualify as an aerial gunner. So, after six or

nine weeks at Tyndall Army Air Field as an aerial gunner, I was sent back to

Tuskegee awaiting assignment for bombardier school. This is a little aside, but,

I developed appendicitis, had appendectomy, went home to Little Rock for a

convalescent leave. Some of my other classmates had been sent elsewhere for

bombardier school, but I came back to Tuskegee and during that time is when a

new co-ed (His future wife Maud.) had come from Arkansas and I met her. This is

a short story, but before I left there they sent me out to Midland

Army Air Field for bombardier training and I guess this was from the fall of

44 to January 1945. That's when I was commissioned as a bombardier. And things

were at that time, that the experiment, "Can blacks fly fighter planes?" was all

settled. And so the military hierarchy decided to go to the next place. Let's

set up a medium bomber, a black medium bomber outfit. So, we're going to train a

black medium bomber outfit and they had trained more bombardiers than they

needed and more navigators, but they needed more pilots and if you had the

qualifications for pilot, you could go leave bombardier and go to pilot

training, and that's what I elected to do. As a matter of fact, my instructors

at bombardiering were Purple Heart survivors of World War II in Europe.

I saw those purple hearts and those bombardiers had nothing between them except

Plexiglas between them and the flack. So I was glad, instead of being put on a

B29 going to the Far East, when the war was still going on, I was sent back to

Tuskegee Institute for primarily flying sponsored by the Tuskegee Institute,

three months of that roughly, three months of basic training flying an AT-6 at

Tuskegee Army Airfield. In my last three months advanced training flying B-25s

at Tuskegee Army Airfield, and I finished advanced training in October 1945,

this is three months or so after the war in the far east ended. So my war time

experience for me was spent in training. But I was a commissioned officer and

earned flight pay, and earned respect being a flying officer, and in this case

with two ratings.

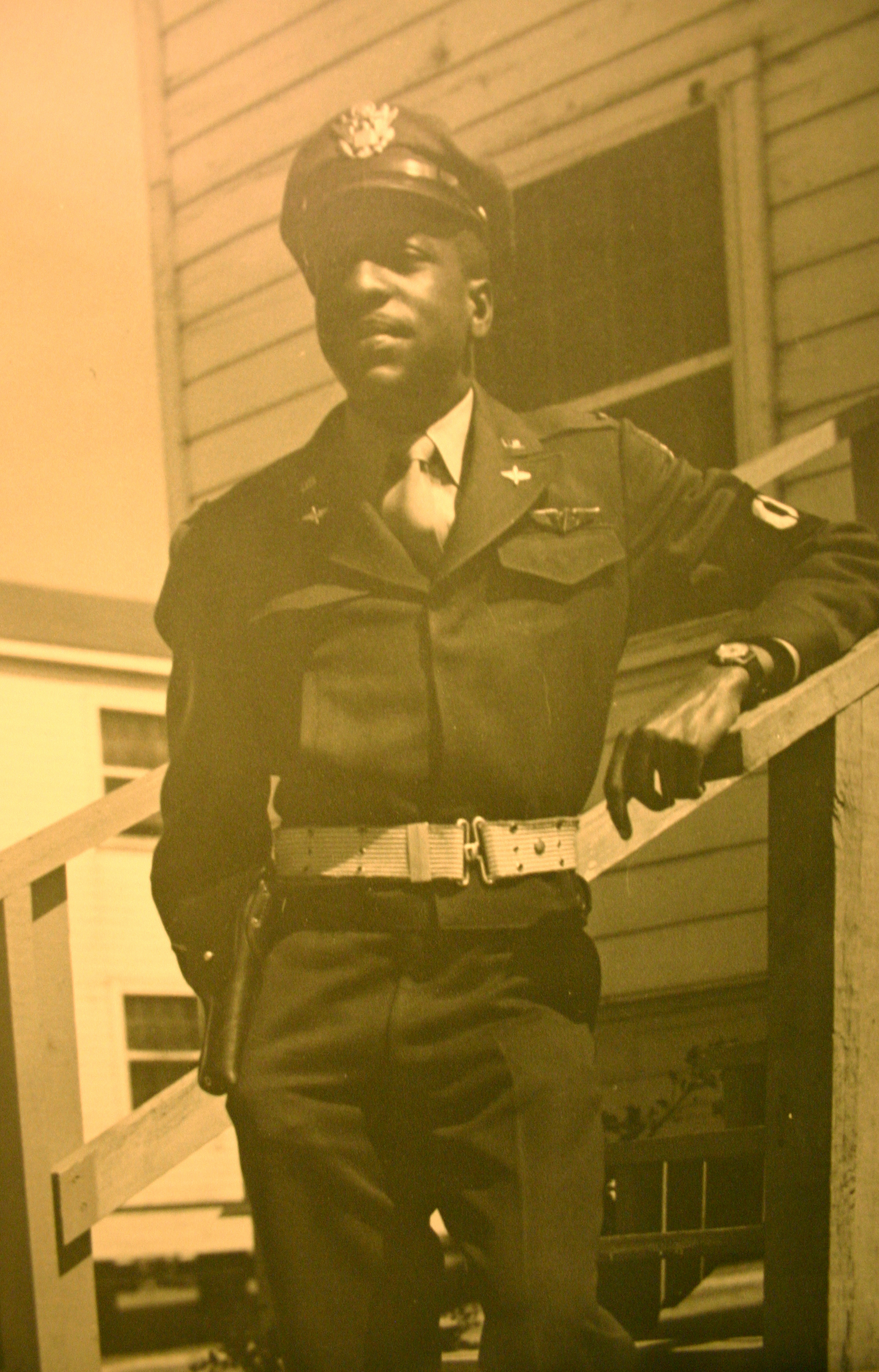

When did you get your flight wings?

The first flight wing was at

bombardier, well, first wings were as an aerial gunner, but this is enlisted

people that were aerial gunners; that was in the fall of '44. In January, I got

the exact date, 1945, I was commissioned as a second lieutenant at Midland Army

Air Field, and so I had new gold bars and new bombardier wings. And I was twenty

at the time. (laughs) I really felt on top of the world. That was sixty years

ago, and that's gone by real fast.

Whenever you were in Tuskegee, was there anyone you stayed in

touch with, wrote letters or anything like that?

Tonight! And tonight

because it just happens one of the people who went through bombardier with me

and pilot training with me is Arthur Carroll Harmon and I'm going to write him

and send him a copy of the newspaper article that was in the Fort Sam Leader

last month. And another fellow who's is in the video, Nicholas Nubley. When I'm

wearing my 45 pistol, officer of the day, he's with me. I've stayed in touch

with him.

Are you in contact with any of the pilots from Tuskegee?

There are

two, and I've been writing to one, over this weekend I've got one in the mail.

One who's on the photo montage there is Nicholas Nebulan, he's in Cincinnati,

Ohio and I call him on his birthday. And another fellow, Arthur Carroll Harmon,

he flew B-25, and he settled in the San Francisco Bay area. So, I kept in

contact with him. Those are the main two people. Plus, an original, what I call

an original Tuskegee Airman, one who went overseas and fought, was Richard

Caesar, and he's now a retired dentist, in San Francisco. And I talked to his

sister the other day and I'm sending him an article that came out in the

newspaper about me. He identifies being a Tuskegee Airmen.