Vilma Salazar (nee Hernandez)

This interview was conducted in Spanish.

Where were you born?

How is life different in San Antonio versus in El Salvador?

The difference is major. In San Antonio, there were actually

breaks. You only had to work the times you were assigned--in El

Salvador you work around the clock. You work non-stop, especially since

we grew coffee. But even when we weren’t tending to the fields we were

doing something around the house. In San Antonio, we had to learn to

relax.

Can you elaborate on that.

We weren't used to it. Ever since I was a little girl I always

had something to do. So it was a big adjustment. I was used to being

told by my mother: This needs to be done by this time, or else. Over

there you listen. There are dire consequences for not obeying your

parents. It is actually looked down upon and you were punished. My

father always let me get away with more than my mom.

What do you mean?

We didn't have any money, but he'd sometimes sneak a colón

or two for me. Believe it or not, that was enough to go to the beach

with my friends and get an ice cream or a soda, sometimes both if we

flirted with the vendor!!

Is that how you met my grandfather?!

Oh, no. Honestly, I wasn't the one doing a lot of the flirting.

My friends were a lot more forward that me. I was always the shy one.

But I still didn't mind getting a free ice cream once in a while!

So how did you meet my grandfather?

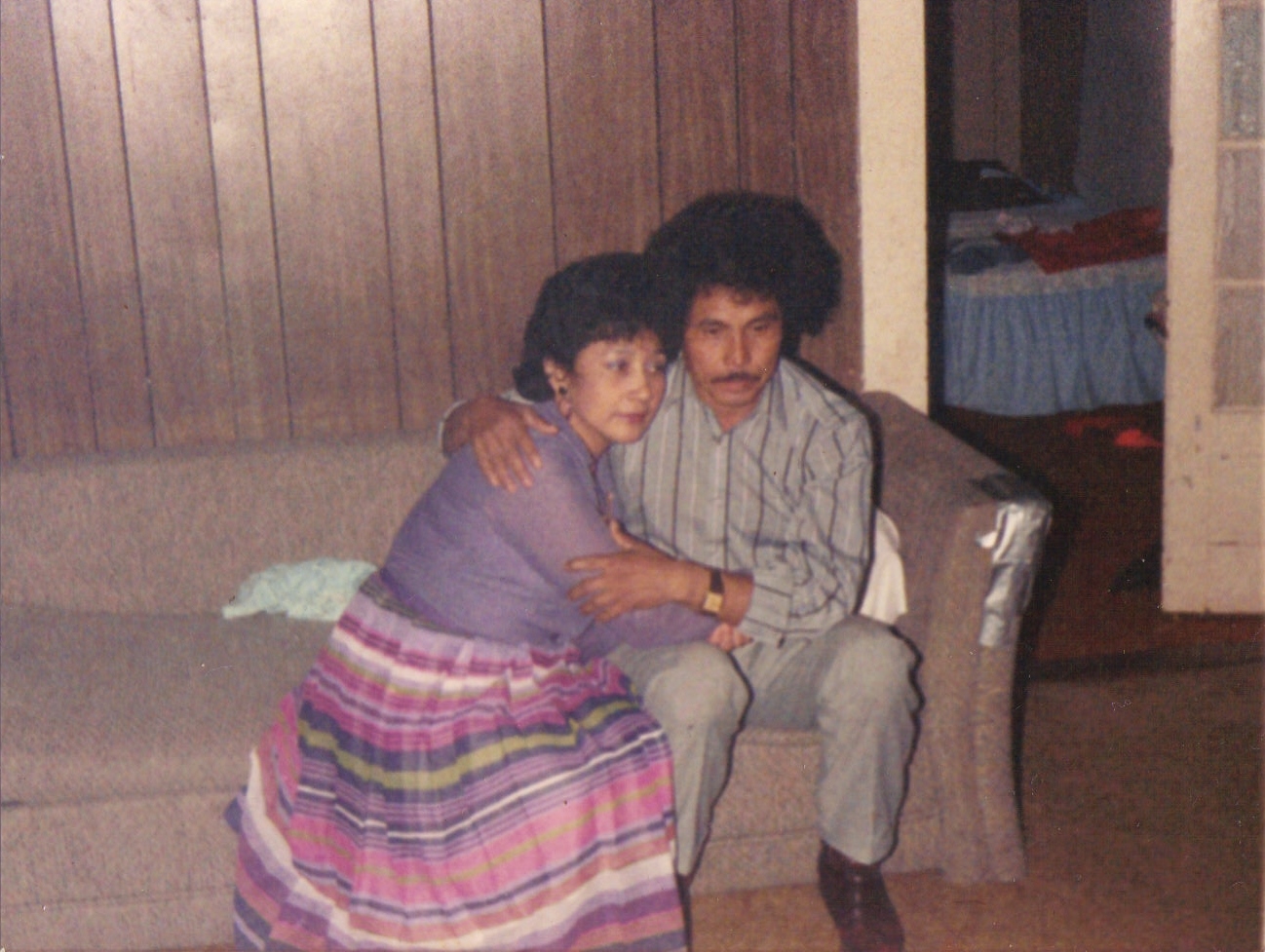

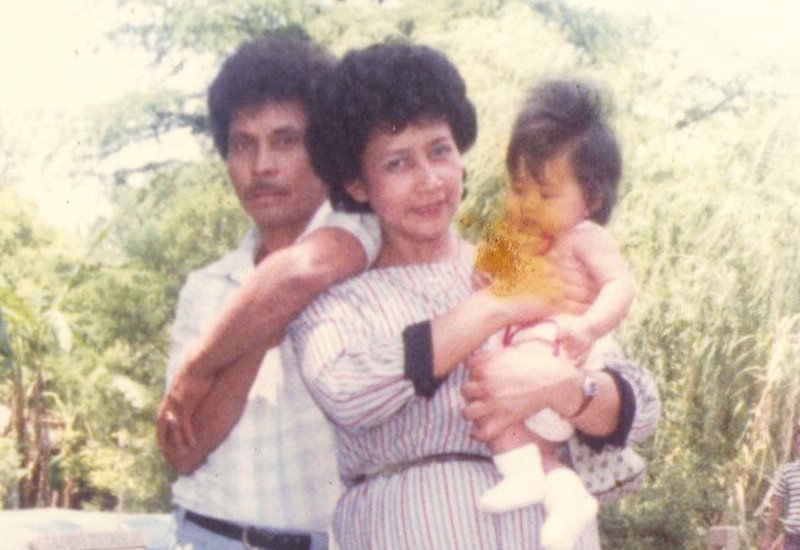

We met through mutual friends. There was a small pupuseria near the Universidad Católica de Occidente

where he attended and was studying to become an architect. I think we

liked each other from the start but I was reluctant because I already

had your Tia Yanci and I didn't want to force him into parenthood. It

didn't matter to him and we started dating. We got married and had your

mother about a year later.

It didn't seem fast to you?

Yes. But we fell in love, and I wasn't going to start disputing

that. I was lucky to find someone that was smart and charismatic and

accepting.

So why did you leave El Salvador?

It was this particular incident that really triggered our desire

to leave. I love my country, but at the time it was dangerous. Many of

us didn’t go out after nine o’clock because we were afraid of the

soldiers that paced the streets! I believe that it was in 1979 that

about five soldiers came into our home and started breaking things,

pointing their rifles in our faces. Your grandfather was especially

afraid of what they could do, especially to our kids. We’d heard of

several execution style murders around where we lived so as you can

imagine we were petrified. We never understood why they targeted us. We

had nothing. Jorge [my grandfather] told them: “We have nothing but

take anything that you want.” They were in our home for about fifteen

minutes, and just left. That was the day that we decided to leave. We

worked and saved up for a year, until we could afford to pay the

Coyote. The ongoing war changed everything.

How was the crossing?

Hard and scary. Your grandfather’s friend Hernan gave us a ride

to Mexico. There we met the Coyote and he explained to us what would

happen. There were about five other people with us. I don’t remember

how long it took or when we got to California, but I do remember being

the most tired I have ever been in my life. We had some family friends

in Los Angeles that let us stay there. Your grandpa called his brother

in New Jersey who sent us money to buy two plane tickets to go to New

Jersey. We left to New Jersey about a month after arriving in Los

Angeles.

Did anything bad happen?

Fortunately, nothing bad happened. Although the darkness is unbearable and so was the heat. We had a couple of close calls with the border patrol,

but we were evasive and everything turned out fine. Although, I had

just had a baby, it was like an immediate diet! I was so thin when we

finally got to Los Angeles.

Was leaving your six children in El Salvador difficult for you?

It was one of the hardest things I’ve had to do in my life! We

hardly spoke to each other because of the long distance fees and

calling cards and whatnot. It was especially hard for me to know that I

had left your Tio Onan who was just a baby. It was necessary, though.

We wouldn't have made it with an infant baby in a foreign country, I

don't think.

What were the downsides to being in San Antonio?

I missed my kids so much. My youngest was six years old by the

time I was able to see him again. Also, I wasn't aware that both of my

daughters had gotten pregnant. I didn't know whether to scold them or

congratulate them!

Did you ever experience discrimination because of the color of your skin?

Oh, God. You have no idea. Especially, since your grandfather and

I were not wealthy or had good jobs. But you know what? We struggled

and we were proud of that. We struggled because we wanted to save all

the money we could. We saved money for two years and were able to buy a

small house, as well as pay for all the immigration papers

that were currently in the process. We had six kids to bring to us, and

by 1986, we had two grandchildren as well. So the fact that people

looked down on us was not surprising to me, but honestly (laughs) I

felt okay about it. They didn’t know any better.

Can you tell me about how the stress of making it finally got to you?

I started getting pulsating migraines. And was frequently having

nervous breakdowns. Your grandfather and I both accredited it to

stress. We knew our children would arrive soon, so we thought that when

they got here all my stress would go away.

What did it end up being?

Turned out that I had a brain tumor. It came as a shock to all of

us. I'm just glad that I had my children here at the time to help me

cope. But at the same time I didn't like for them to see me that way.

They had to operate almost immediately. The surgery was successful,

although the operation resulted in nerve damage. It was an ugly

experience, but by the grace and mercy of God, I made it through

alright.

When you finally acquired the money, and your

children were free to enter the country what was your reaction, how did

it all happen?

By 1986, everything was perfect. We could legally go get all our

kids and bring them to us. Your mother was having difficulty deciding

whether or not she was going to stay since she wanted to try to work

things out with your father, after all you were just a month old at the

time. So your uncles were the first to come, my baby, too, who had

turned six without me being there, and didn’t even remember me when he

got here. But those were sacrifices that had to be made. When your

parents’ relationship fell through your mom decided to come. So we sent

for her. We told her that we would send for her and then for you, but

she said that she wouldn’t leave without you. With the news that your

mom was leaving, your dad wanted to keep you and your parents got into

a bit of a custody battle, later that year we had enough funds and sent

for the both of you. Your Tia Yanci didn’t come until 1991.

How did you first feel when you saw your children?

First, I just thanked God, that they all got here safely. Then we

all talked an reminisced and ate. It’s a good feeling when all your

struggle is finally worth it.

What do you miss the most about El Salvador?

Oh, the beaches, the air, almost everything. There is so much

that is great over there. The major difference there and here is the

closeness of the family. Over there, all our family lived down the

street from each other. Here, there is so much separation. I have a son

in Dallas, family in Los Angeles and some relatives in New Jersey. I

don't feel as close as I did over there.

Do you like living here?

Frankly, I've assimilated. I've gotten used to living here. I've

got my own home. All my children are here and my grandchildren, and my

great-grandchild. But by no means do I like living here, although I'm

content.

Is there anything that you would change?

Yes. I don't like that half of my grandchildren don't speak

Spanish, although their parents do. If there is anything that I would

like to leave after I'm gone is some sort of legacy. My language could

be it. I think its very important to be wary of your culture, and

appreciate your heritage. I've depended on it for so long, and to see

my future not realize the importance of it bothers me deeply. To answer

your question: I'd like all my grandchildren to speak Spanish, not just

understand it.

What would you like to be remembered for?

I'd like to be remembered as a good person. A loving person, someone who knew better!

Universidad Católica de Occidente is the website of the University that my grandfather attended.

Pupuseria Information and definition of a pupuseria.

El Salvador - Travel Information on traveling to El Salvador.

El Salvador's currency Information on El Salvador's currency the colón that was used from 1919 to 2001.

Civil War in El Salvador Information on the civil war in El Salvador that is said to have begun in the 1930's.

The Border Patrol Official website to the United States Border Patrol.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Official website to immigration services.