Lydia Nevarez (nee Maltos)

|

|

I interviewed my mother Lydia Nevarez (nee Maltos). Lydia was born on October 13, 1951 in Crystal City, Texas. She is the third of four daughters of Victor and Belen Maltos. Their other daughters are named Santa Garcia (nee Maltos), Norma, and Laura Costilla (nee Maltos). Lydia was born and raised in Crystal City. When she was younger, Lydia says that she and her family traveled every summer to Chicago and Mexico where other relatives lived. She attended school in Crystal City until she graduated from the local high school (Crystal City High School). After graduation, Lydia attended Southwest Texas State Junior College in Uvalde, Texas for two years. She then transferred to San Marcos where she graduated from Southwest Texas State University with a teaching degree. She has been teaching now for 30 years. On June 11, 1983, she married my father, Armando Nevarez, who also grew up in Crystal City. They stayed in Crystal City and had three daughters together. In 1992, they all moved to San Antonio where they have lived for over 10 years now.

What was the cause of the walkout of the students of Crystal City High School in 1969?

Actually, it started the year before with the graduating class of 1969. When they graduated towards the end of the year we started hearing a group of students that began saying, "Next year when school starts again you should really consider doing something about the way the cheerleaders are selected, the way school favorites are selected and the way the homecoming queen is chosen because it's not fair."

How were the chosen?

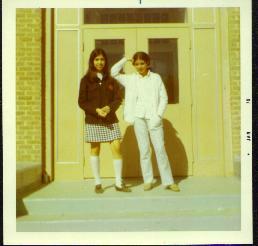

They would tell us that the favorites like the most representatives and most beautiful, especially the most beautiful, were chosen by movie stars!

Like who?

Tab Hunter and oh, I don't know… I would have to go back to my yearbook and check but they would say that they would send the pictures off to Hollywood and one of the movie stars would select the most beautiful, which was not true. The favorites would always be an Anglo. For cheerleaders, it would always be four Anglo girls and one Hispanic.

And the school was predominately Hispanic, right?

Yes it was. And the Homecoming Queen issue was really what started the whole walkout of '69.

Because of…

Because they gave all the girls in my senior class, and I have the little paper, that said if you were the daughter of a Crystal City High School graduate you would be eligible to be nominated or to be a candidate for Homecoming Queen, which left out almost all of us because the majority of our parents had not graduated, maybe a few of the Anglo girls. So we took that paper and that's where it all started with that little paper that was passed out.

Along with that, what else were you protesting and what changes did you all want to see happen?

We felt that over all we didn't have enough representation in the school. We wanted more Hispanic teachers, we wanted more counselors that were Hispanic, we wanted to be treated equally, and one of the basis at that time, we were saying that we were being discriminated against. And that encompassed the way that the student favorites, the fact that we didn't have enough Hispanic teachers, and I remember so clearly that we were not allowed to speak Spanish at that time. It was all English.

How was this organized? How did you all come together to decide to walk out?

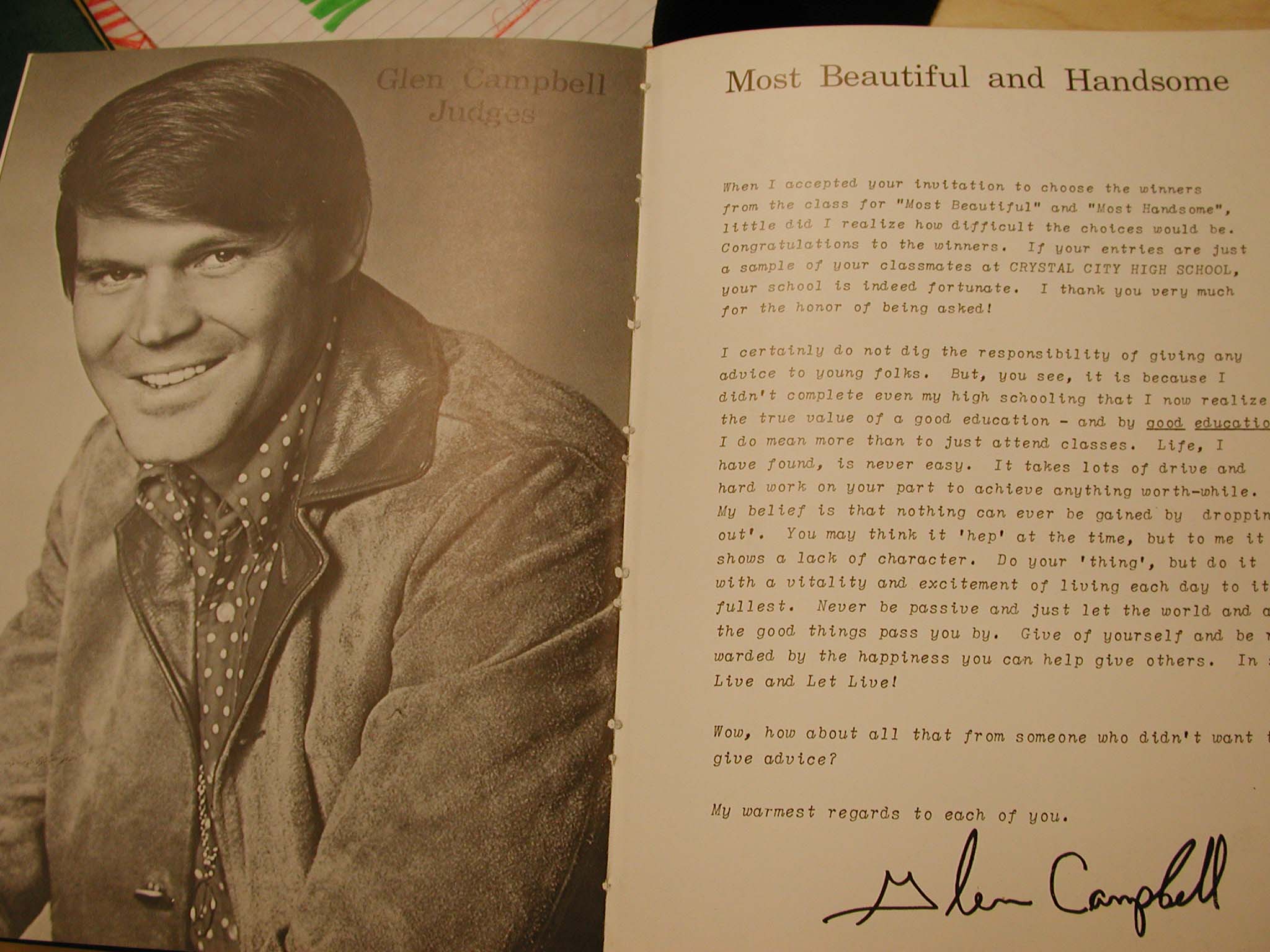

It started really with a group of students, Severita Lara, Mario Trevino, Diana Serna. They really started talking to other students about this. They said, "You know what? We're going to have a meeting at this place and there's this man who says he'll help us." I had never heard of Jose Angel Gutierrez. My parents had, they knew his dad and his mom. At that time, Jose Angel was very young, he had just graduated from college, I think he was 20-something. And so they said, "We're going to go to his house tonight and we're going to talk about doing something like they told us last year to do something about this." So I told my mom and dad and they said, "Yeah, go ahead and go." So we did, and that informational meeting, the first meeting we went to, he was there and he said "If you all need help, here's how to start. You need to get together and inform all the students and they're going to let you meet at school so what I'm proposing you all do is type a letter. I have a mimeograph machine (a copy machine). Draft up a letter listing all your demands saying, 'This is enough' and pass it around school."

That was our way of getting the word out. It took several meetings we didn't do it all that night and drafting up something. Then we passed it out to all the Hispanic students in our high school. Rumbling started to go into the school, teachers got a hold of the flyers and I remember right before we did the walkout we all wore black arm bands that we passed out. We said that signified equality was dead. I remember Jose Angel told us before we passed out those papers he said "There's a chance you could get expelled if they find out who started this."

And you were part of this group that started it?

Yes, I was part of it. And we said, "Well it's ok." And he said, "Don't worry, if you're expelled, I have a number of a lawyer who can help us." So we felt very confident. At that time, you're that young and you have the support of somebody who's a college graduate, you know you have a lawyer, and we all felt good about it. I remember talking to my parents and they said, "Fine" you know because they had already heard about it from my sister who had graduated in '69. She had said that something was going to happen next year. So it wasn't something that they were surprised about, they kind of already knew about it. The only thing my dad said was, "You know there's a chance you might not graduate, but if you want to do it, you go right on ahead because in my eyes, it's something that is not wrong."

So what was the final straw that lead to the walkout on December 9?

There had been several school board meetings that were going on before, but on the night of December 8th, the superintendent at that time said, "There is no discrimination and no issue for us to even consider." So the following morning was when we decided, let's go ahead and walk out.

How did it happen? Did you just walk out?

Well, the night of the final school board meeting, a group of us were waiting outside of the administration building and when they came outside and said no, they said, "Just tell your friends that tomorrow just walk out". And what that meant was that we just didn't report to class. We didn't even go inside the building. That first day, some of the students didn't even know about it. Some of the parents came and got the students out, others just walked out of their classes.

What did you do?

I just didn't report to class. And every day, the numbers [of the students] kept increasing until we had almost all of the students out of the school. It started off with 700, then 1,000, 1,675, 1,703… I think that was the final number of students on December 18th and 19th.

What was the feedback from the community? What did they think about all that was going on?

We had a lot of support from our parents. They would congregate in front of a small grocery store, an IGA store that was across the street. They would tell us they were there just in case things got out of control.

Did things ever get out of control?

No. Everything was always very peaceful. Students were there, parents were across the street, they did not come onto the school grounds. We'd march around the school,

sometimes down the street, downtown also. There would always be people there from the little town newspaper taking pictures, doing interviews and basically we would just hang out there at school.

What was the negative feedback?

The negative feedback was from a lot of the businesses, which at that time were run by Anglos. They wrote letters [to the local paper] that were very negative and said that maybe some of this was not the students, but Jose Angel Guiterrez who was trying to work through the students to cause trouble. I remember one of the students [who walked out] got fired from his job; the owners said it was bad for business. So we boycotted the store. At that time, I also worked after school and my boss was not Anglo, but Hispanic. I told him I was going to walk out and asked if he thought it was going to affect his business and he said no. But his wife approached me and said, "Your parents let you walk out?" I said, "Yes Ma'am." And she said, "Well, I'm not going to let my boys walk out." I remember other students lost their jobs too and those businesses were also boycotted.

This event cause national attention. How do you feel this event was depicted?

I think it was positive because it was the first time that something like this had been done by Hispanic students. CBS came, they did interviews and I know that the three that started this went to Washington, D.C. and they talked to Senator Ralph Yarborough. We had professors from St. Mary's University come and do a "teach in", the "open air classrooms" is what they called it. There was a Dr. Miller from St. Mary's University and they would meet at the Crystal City Park, and they would tutor students. For us, it showed a great amount of support because I think it made our educators look non-caring and these other professors who were coming from St. Mary's kind of said, "Ok, we'll sit down and we'll work with you so that you don't stay behind in your studies." I think that shows a lot. I think it spoke volumes for our cause that they would do something like that.

How long did the walk out last?

It stared December 9th [1969], and ended January 6th [1970].

How did it end?

It ended after the last school board meeting on January 5, 1970. At that meeting, they had five students, five parents, two Justice Department officials, and two U.S. Civil Rights Commission representatives. They again reviewed all of the demands of the students. My dad was one of the five parents that were selected to be there. He took notes on things that were discussed.

Were all your demands met?

Yes we received what we wanted and even a little bit more.

How do you think this event changed the school's policy on the way things were run?

I think it changed it tremendously; it made a big turnaround. I think it was a wakeup call that was long overdue. Like they used to say when I was in school, "The sleeping giant woke". The students were demanding rights that were legally ours in the first place. When I was there, the administration like the principals and counselors were already there, so the changes didn't start to occur till after we left. We really didn't see anything that year. A lot of Anglo teachers and families left because of the walk out and that left a lot of room for recruiting new teachers, Mexican-American teachers for our Hispanic population. Now, we see the result of the walk out. There is bilingual education, more Hispanic representation in the schools… it opened the door for more opportunities for our people.

During the walkout, the community was divided over this issue. Was this still the case after the walkout ended?

Oh yes. There were still a lot of opened wounds when it ended. The Chicano population had won and then there was the politics. People started saying, ok, we can change the schools, we can change the city council, we can change the school board. So then it started cutting deeper into the community faction. It wasn't just the students anymore, now it was let's do the city, the county. And then when they started going into the politics, it turned into, let's form our own political party. Jose Angel Gutierrez filed an application for a new party, La Raza Unida Party in 1970. At that time, he was 25, ran for the school board and won by a landslide. Young people in their twenties began to run for city council and won. Within that year, the city council and school board were reformed because of the walkout and because of the awareness of "see what we can do if we work together, we can make changes".

Were you involved in this movement?

Yes, Jose Angel encouraged those of us who were involved in the walkout to help recruit people to vote cause a lot of people were scared to go and vote. So we went house by house explaining the ballots to the older people and to encourage them to vote and to help provide transportation for them if they did not have a way to make it to the polls. It was an exciting time for me because I was a part of it, not just with the school, but also with the city government.

Is the Raza Unida party still active today?

No it's not, but I feel that the Raza Unida, or the United Mexican American Race, is doing well for itself. I think a lot of the students that went through this turmoil are educated now and they know that we can make a difference. Because of bilingual education, because of exposure made possible by Mexican Americans, we do get our message out there. I think this all came about maybe, I hope because of all the turmoil that happened in that little town maybe kind of spilled over and made a difference. I know that a lot of my friends moved from Crystal City and I'm sure they are encouraging their children to not just take a backseat and say, "Ok, well, we'll let the Anglos take over", you know? For that reason, I think we don't restrict ourselves to that one label, La Raza Unida, we can go across and say I might be a Democrat, I might be a Republican, but I can still stand up for my people.

What happened to Jose Angel Gutierrez?

After the walk out, he got on the school board, and made a big difference there, and then he became a county judge. He did a lot for our community.

How do you feel this experience changed your life at an age when teenagers were very easily influenced by so many things?

It made me feel like I could be a part of something that if there was something wrong that needed to be changed, that there was a way to do it. It really influenced my way of thinking because I remember when I was little I went to school, but wasn't allowed to speak Spanish and I asked my mom why and she said, "Well, those are the rules." And I remember going to my grandmother's house and my mom told my grandmother that I was going to be in the walkout and she said in Spanish, "Mijita, pero ellos son los de poder," meaning, "they are the ones with the power, we really shouldn't do anything". And my mom said, "No, but that's not right, times have changed, things need to change." I had strong parents who believed in change, so their support had a tremendous impact on me. They said, "Ok, if changes need to be made, then you need to do it and we'll back you up." At that young age, it made me feel like we're right and no one could tell us otherwise… I felt very empowered.

If you had the chance to do it all over again, would you?

Yes because I had the support that I needed at that time and it was something that I believed in. It was something that I saw firsthand that was wrong. And I would encourage anyone who believes in something that is right that they feel they can make a difference to do it. I think there are no barriers when you feel something is wrong whether it be in education or at a higher level, and if you find resources to back you up, then you can make a difference. I would certainly do it again and would encourage my daughters or friends if they ever found themselves in a situation where they know they can make a difference to do it. I think this has made me a stronger Hispanic woman and I think it has changed the way I look at things. So yes, I would do it all over again, in a heartbeat.

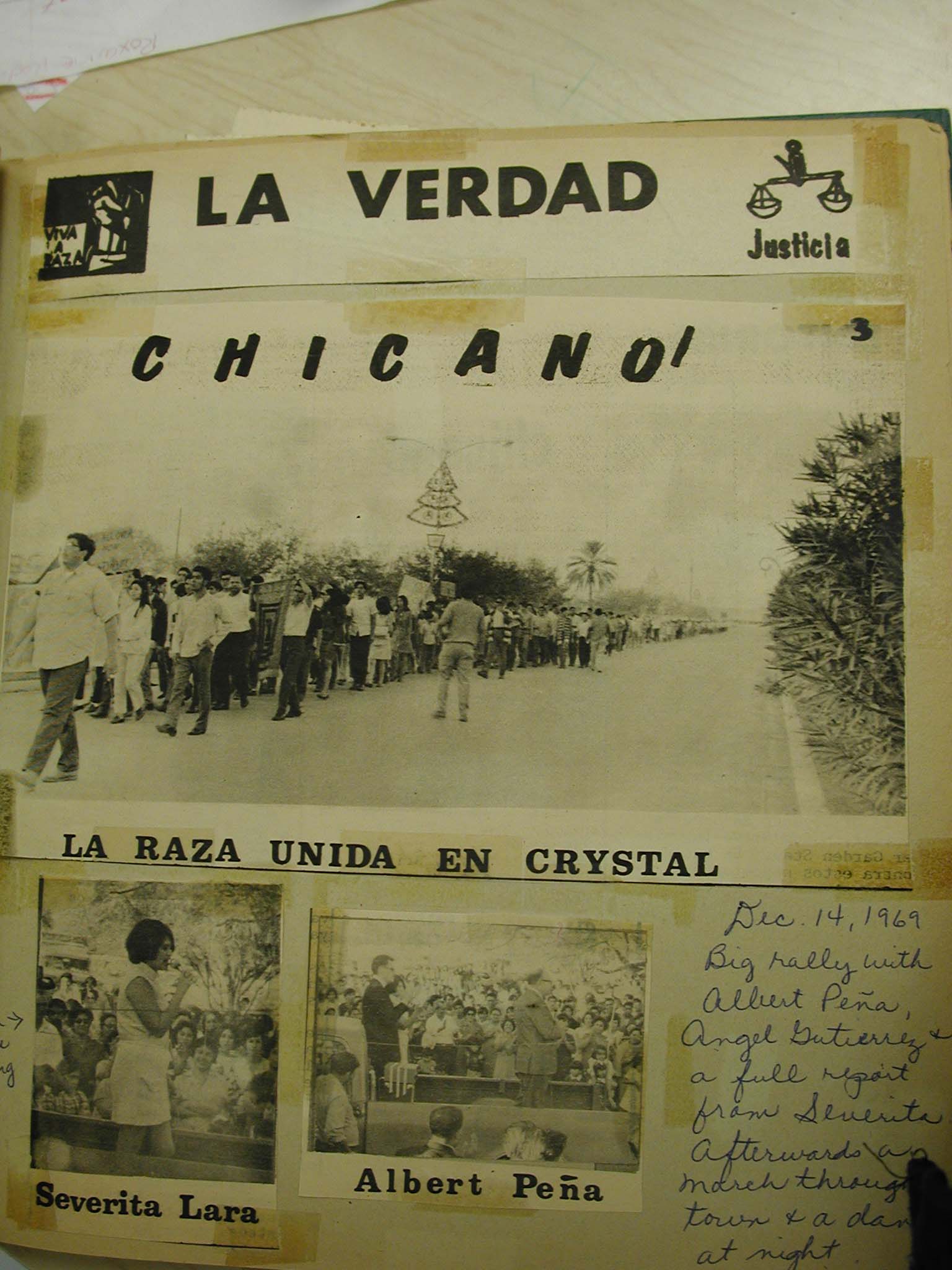

I learned so much about my mother's past and her involvement in a very important historical event that I did not know too much about before. I did not realize how passionate she was about this cause. I had always seen her scrapbook around the house (mostly in our garage), and I never understood what it was about. I remember not even understanding what the words "Raza Unida" meant. I remember her trying to sit my sisters and I down so that she could tell us the story about this event, but we were never interested. Now that I'm older and understand more about civil rights issues, I was so amazed to learn about my mother's participation in this movement. The entire process of the interview was a brand new experience for me. I enjoyed hearing and watching my mother remember the things she went through and seeing how proud she was to have been a part of that and also happy that I was finally taking interest in this event that was so important to her.

Odintz, Mark.

Handbook of Texas Online: CRYSTAL CITY, TX. Handbook of Texas Online http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/CC/hfc17.html/ (2000).

The profiles and histories of every Texas town and city are documented in this site. Statistics and facts are included in this site.

TabHunter.com : The Official Tab Hunter Website . 2005.

UTA Libraries Online.

Tejano Voices: Professor Jose Angel Gutierrez. University of Texas at Arlington Center for Mexican American Studies Oral History Project http://libraries.uta.edu/tejanovoices/gutierrez.asp/ (2003).

This University of Texas at Arlington Online Library profiles Jose Angel Gutierrez as a professor at the university. There is also mention of his life accomplishments, including the Mexican American movement with the Raza Unida in Crystal City, TX.

CBSNews.com. CBSNews.com http://www.cbsnews.com/sections/home/main100.shtml/ (2003).

The website belongs to the news station that went to cover the story of the student walkout in Crystal City, TX in December, 1969.

St. Mary's University. St. Mary's University, San Antonio, TX http://www.stmarytx.edu/ (2003).

This is the homepage to St. Mary's University, the university that professors came from (in San Antonio) to tutor students who missed out on classes during the walkout. This site provides an overview of the school's academic course, dorm information, as well as activities students can be involved in at the school.

Printed Source

Many articles from old issues of TheSan Antonio Express News, The San Antonio Light, and The Sentinel newspaper in Crystal City, Texas were used as reference for this project, though there were not any specific issues or dates that can be used to record.

Maltos, Lydia; Raza Unida Party 1972 Scrapbook, December 9, 1969-January 6, 1970.