John Allen Shull, Sr.

![]()

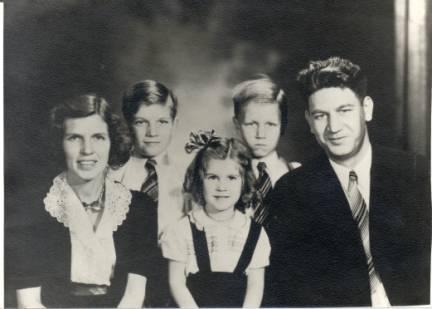

John Shull (dark-haired boy) and family as war broke out

Interviewed at his home in San Antonio,

Texas

April 1, 2007

Katie Shull

History 1302, Palo Alto College

World War II: The Homefront

John

Allen Shull Sr., my grandfather, was born on May 12, 1931, to Aytchmonde Perrin

Shull and Maybelle Pickens Shull. He grew up with one brother and two sisters.

Although my grandfather was born in Bloomington, Illinois, he grew up in Willow

Springs, Missouri, Macon, Missouri, and Lowpoint, Illinois. Throughout his life

up to now, he lived in Peoria, Illinois; Harlingen, Texas; Wichita Falls,

Texas; Tachikawa, Japan; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Fuchu, Japan; Bangkok,

Thailand; Nakhon Phanom, Thailand; and San Antonio, Texas. While he was in the

U.S. Air Force he saw many other places in the United States and Asia.

My grandfather graduated from Bradley

University in Peoria, Illinois, with a B.S. degree in political science.

Throughout college he worked fulltime at Caterpillar Tractor Company and some

other odd jobs. He became an Air Force Officer because he was in the ROTC in

college. He married my grandmother Ellen Murphy on May 15, 1957, at St.

Bernard’s Church in Peoria, Illinois, when he was twenty-six years old. Even

though all his family were Democrats (and his Uncle Frank Briggs was briefly in

the U.S. Senate and later in the Department of the Interior), my grandfather at

first was a Republican, but he is now a Democrat.

Papa enjoys playing the stock market, reading, playing

board and card games, watching television, and enjoying his grandchildren. He

used to enjoy traveling, but his health now causes him to stay at home. He was

born in the Great Depression and lived through World War II as a child. Even

though he was young, he followed the war and understood what was going on in

Europe and the Far East.

Papa, how old were you when Pearl Harbor was bombed? Where

did you live? Who were your parents? Did your father have to go to war?

I was 11 years old and lived in Macon, Missouri.

Aytchmonde Perrin Shull and Maybelle Mary Pickens were my parents. Because he

had three children he didn’t have to go to war. My youngest sister (not in the

picture above) was born at the end of the war.

What

were you doing when you heard Pearl Harbor had been bombed? And what were your

thoughts about it?

We had been out rabbit hunting, and we didn’t get

anything. We came back home and we found that Japan had attacked.

It kinda scared me. I didn’t really know what being at war meant at the time.

How did your life change because

your country was at war?

My life changed because there were a lot of scarcities

in the country. Sometimes we couldn’t get all the meat we wanted to eat. We

couldn’t get all the gasoline we wanted. So it cut into some of our activities.

Life really changed.

That was the ration stamps and stuff

like that?

Yes, we had rationing. We had ration

stamps for meat and other things that were in short supply. We had coupons

for gasoline but not all we wanted. The same was true for tires for our car.

These things were needed for the war itself. Sugar, bananas, and other things

imported usually were in very short supply. We used honey for sugar. We were

limited in the shoes we could buy.

Did that upset you?

Yes, of course it did, but it didn’t make anyone

angry. We were not able to get all that we wanted, but we could get all that we

needed if we were careful not to waste. Patriotism was very strong. We knew we

were sacrificing to help win the war.

What did your parents, your teachers,

and your friends tell you about the war, especially when it started in December

1941?

They told us that Japan attacked us illegally, and

that they were the aggressor, and we had to fight them to keep our liberty.

As the war went on, what were people

at home asked to do to help the United States win the war?

Well, we were asked to do a number of things. We were

asked to grow victory

gardens – all kinds of vegetables that we could grow and eat. Then these

things did not have to be transported to the stores. We already had the fruits

and vegetables from our victory gardens. We were asked to conserve gasoline as

I told you. We were also asked to collect foil and other things to send it in

so they could make war materials out of it. Another thing we did was we went

out and collected kapok. Actually we collected thistles that the government

made kapok fiber out of which was used to make flotation devices, life vests and

things like that.

What about the women, didn’t they

have to . . .

The women in WW II, many, many women went to defense

plants and made airplanes and tanks and ships. They took the places of the men

who were at war. People were surprised they were so successful. Some of them

stayed in their jobs after the war but not very many. They were expected to be

wives and mothers at home.

What about ration stamps? How did

they work for your family? Did you hear any unusual stories about using them?

No, all I know is that we had less meat to eat because

of rationing. We didn’t have much in the way of sugar. We had to use honey in

coffee and things like that. Coffee was scarce . . . and what was the question

again?

Do you know any unusual stories

about using them?

Oh, yes. We heard unusual stories. A lot of people,

they were called hoarders. They would get in and buy all sorts of foodstuffs

and things like before other people had a chance to buy. There was some dealing

on the black

market which meant that if you had enough money, you could buy things on

the black market that you couldn’t get in a store legally.

What were victory gardens? Did you

have one?

Victory gardens were vegetable gardens that we planted

and cultivated and grew ourselves. We had tomatoes, corn, peas, beans, okra,

you name it, we had it. My mother

canned a lot. She canned berries, she canned tomatoes, she canned even potatoes

which we used when there were scarcities, when we couldn’t buy them at the

store.

Did you ever have trouble getting

the supplies your family needed during the war?

Well, we had scarcity, but we generally got what we

needed.

Just not as many things as you

wanted?

We’d only eat red meat maybe once a week instead of

having it two or three times a week. We had Meatless Tuesdays and we ate fish

on Fridays. All this was done to conserve meat for the men overseas fighting

the war.

Do you remember any of the posters and cartoons during the war? Tell me about them.

Yes, there were several notable posters. One was a

great big poster of Uncle Sam with his finger pointing at you saying, “Uncle

Sam needs you.” That was for the younger people, the younger men, to stir them

to enlist.

Another one said, “Loose

lips sink ships.” Another was “Buy Savings Bonds” or “Buy

War Bonds.” Those were bonds that the government used to issue to pay for

the war.

What about the movies? How were they

different during the war?

Well, there was a plethora of anti-Japanese movies and

stories about us beating the Japanese. We pictured the Japanese as brutes

little better than animals with these huge, terrible grins spread across their

faces. Well, at least they were huge up on the movie screen. I remember “A Guy Named Joe” with Spencer

Tracy. Also “Meet Me in St.

Louis,” I think came out during the war.

What songs do you remember during

the war?

“Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition.” Let’s see,

what else did we sing? “Over There” came back in vogue. (sings) Over there,

over there, over there. I also

remember “As

Time Goes By” and “Coming in on a Wing and a Prayer.” Oh, and there boogie

woogie songs too like ‘Rosie the

Riveter’ and ‘The

Bugie Woogie Bugle Boy’ .”

What did it mean to be a Gold

Star Mother?

We could tell which houses had someone serving in the

military because of a flag placed in the window. It was five or six inches

across and maybe ten inches long. There were blue stars for those serving,

saying that they had one, two, three, or four sons in the military. At some

houses there was a flag with a gold star. This was for those who had lost their

loved one, those who had been killed. The gold star

mother was the mother of the soldier that had been killed.

How did the people of the United

States do their part to help pay for the war?

We bought savings bonds or war

bonds. Children like me bought savings stamps. If I bought $18.75 worth of

stamps, I could get a bond. So we did that, and we conducted various drives for

the government. We participated in drives for metals and other items that the

government vitally needed.

John Shull after WW II in 1946

What did you know about the Japanese

Americans that were put in prison camps?

We thought that was a terrible thing to happen to our

Japanese-American citizens. They were American citizens that were taken out of

their homes and put in prison camps, an act that is unconstitutional. And we

felt it was a great misdeed that had been perpetrated against the

Japanese-Americans. They were the only ones, the only foreigners that were put

into camps for the most part. Very few Germans and very few Italians were put

into camps, and they were our enemies during the war.

Did you know any friends or

neighbors who had sons in the war? Did you ever see any of the V-Mail letters

that came to families from fighting men overseas?

Yes. Yes, I did. They were blue, and they were very

lightweight. During the war, stuff coming from military people in the theaters

of operation was censored.

Did you ever hear of the Japanese

firing on the United States? How did that news make you feel?

Well, it was scary when the Japanese submarine shelled

Los Angeles. I think they fired five shells into the United States. Also, they

sent weather-type balloons across the ocean into the Pacific Northwest hoping

they would explode and set trees on fire. One such balloon did explode, and it

killed four or five people in Washington state, I believe.

Tell me about the German prisoners

that worked near your home.

They were German prisoners of war that we captured in

Africa. And they were brought – they were given projects to work on to keep

them busy. And there were German prisoners that worked in our area. They worked

on dikes, building them up so we wouldn’t have floods. They were just like

American troops. They looked the same, but they were guarded. They had

guards that were with them so they couldn’t escape.

Where did they live?

They lived in POW camps. There were several around the

country.

How

do you think the war was different for people living in the country and on

farms, as you were, compared to the city?

I think it was much easier for people living on the

farms. We could grow our own gardens, we had plenty of room, we could even

raised our own pigs and calves and had them slaughtered. So we had more meat to

eat than those in the cities. We had sheep and some pigs and chickens. We ate a

lot of chickens because we had a chicken house. I collected eggs. Then when we

wanted chicken for dinner, I’d go out and catch a chicken, wring its neck, and

pluck it. And then my mother would cook it.

Did you ever see any wounded

soldiers?

Yes. The first wounded soldier I saw was in the

barbershop in Lacon, Illinois. He had been wounded at Tarawa (or Tar áh

wa—however you want to pronounce it). He showed us the wound in his shoulder

where he got hit with a machine gun bullet, and he showed us another wound in

his thigh where he had been hit by a rifle bullet. He was on crutches. And he

came in to get a haircut because he was on leave. So I saw him and listened to

him talk about the war in Europe.

Looking back, what bothered you the most about the war?

Well, we were restricted in many respects. We couldn’t

do all the traveling that we wanted to do. We had problems getting tires. We

had problems getting enough gasoline.

Yes, we were restricted in many ways. But we understood why we were

restricted and felt very patriotic when we were able to do something to help

the war effort.

And also having to see the people

treated – like the Japanese – we treated them terribly?

There was a lot of anti-Japanese feeling in the

country, mostly, I think because the press had dehumanized the Japanese and

made animals out of them. But my Dad said, “What is happening to the Japanese

in our country, to American citizens, is strictly unconstitutional.“

Is there anything else you would

like to add to this interview?

Yes. Personally, I thought that I was going to grow

up, be drafted, and have to go to war. And I didn’t want to do that.

ROTC

cadet, Bradley University

ROTC

cadet, Bradley University

You got lucky?

But I was always a little bit too young to get

drafted. When the war was over I was only fifteen. So, I didn’t have to go.

Anything

else?

Yes, I didn’t think I ever would join the military,

but when I went to college I got into the ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps)

and got my commission and became part of our armed forces. I think that is

rather unusual, no, probably ironic is the better word.

Air

Force officer in Thailand during Vietnam War

Air

Force officer in Thailand during Vietnam War

Anything

else you want to add?

Yes. I don’t like war. It causes too many

dislocations. It causes too many people to be hurt and breaks families apart.

And it causes too many people to be killed. Our country should do everything –

in fact, every country should do everything possible – to preclude having to go

to war.

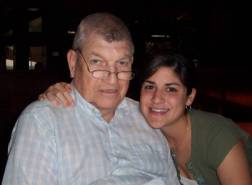

Interviewee and interviewer

Interviewee and interviewer

Analysis

I learned a

lot about how my grandfather’s life was lived, all the places he lived, and

maybe why he is the way he is now. My papa was very mellow about talking about

World War II because it has been a long time since this war. His stories taught

me a lot about how a child growing up in the United States in the early 1940s

had a very different life from my own. I didn’t have to verify anything he told

me because it was all personal stuff and I believe my grandfather. I believe

the most important point made was that there should be no war ever.

Learning about

the past with the interview process takes me back to that time with a real

person. Drawbacks might be hearing the way people had to live with hardship and

I have never have had to, so maybe I don’t understand it as well as I could as

a result. Oral history is a great way to learn about the past because we hear

real stories from real people who were really there in another time and place.

Annotated Bibliography

Bailey, Ronald H. (1977). The

home front: U.S.A.

New York: Time-Life Books.

The changes in life for all the people at home are

discussed here. Rationing is a big issue because of some cheating and the

activities of the black market. The system of the ration stamps is discussed.

Women took the place of men in the factories.

Bird, William L., Jr. and Harry R.

Rubenstein. (1998) Design for victory: World War II posters on the American

homefront. New

York: Princeton Architectural Press.

The best element of this book is the pictures of all the

posters because that gives us a sense of what it was like at home during World

War II. Posters were a way to get the message to the people of what they should

and what they should not do. There are more than 150 drawings in the book,

courtesy of the National Museum of American History and the Smithsonian

Institution. The authors tell the story behind the pictures.

Gluck,

Sherna Berger. (1987) Rosie the riveter revisited: women, the war, and social

change. New York:

Twayne.

Oral histories of ten women are collected in this

book. They worked in defense factories in California. Some of them went to work

to help the war effort, but they also enjoyed earning the money and being

financially independent. The women talk about family history and give their

opinions.. For one woman this book was her only chance to talk about this

chapter in her life; another wanted to make sure the housewife's story was

heard.

Lindeman, Richard R.

(2003) Don't you know there's a war on?: the American home front, 1941-1945. New York: Nation

Books.

The disaster of 9/11 caused the author to remember Pearl

Harbor. Lindeman talks about V-girls and V-mail, and blackouts. He discusses

the internment of the Japanese in detail, but he also points to the advancement

for African-Americans and women,

World War II with Walter Cronkite, Volume 8, The home front and

victory. (1983) 90

min. CBS video. VHS 942.014 KIN.

This is an excellent video because it shows how the

war affected people at home while also connecting with the war itself. Viewers of this video will come to a better

understanding of how World War II affected ordinary Americans and also see the

end with victory. There are other videos in this series that show the war

itself.